In his excellent book, Eating Animals, Jonathan Safran Foer acknowledges the role food plays in culture and family. He writes of his grandmother, a Holocaust survivor who expressed her love by feeding her family and making sure each of them had enough — more than enough — to eat. She was, Foer says, “The Greatest Chef”: “We believed in our grandmother’s cooking more fervently than we believed in God.”

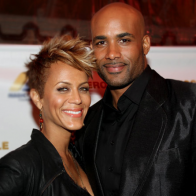

Foer eloquently calls food the “handle” we use to hold cherished memories. When I decided to transition to a vegetarian diet, I worried about losing the handle that connects me to my family (My grandmother and mother are truly the greatest chefs — all due respect to Foer’s Nana.) and to my culture (Southern African-American foodways that include meat). Though I am working toward a vegetarian and not vegan diet, thank goodness for Tracye McQuirter, vegan, nutritionist and author of the best-selling book, By Any Greens Necessary, “a revolutionary guide for black women who want to eat great, get healthy, lose weight and look phat.” McQuirter recently spoke to me about overcoming challenges to a vegetarian diet, including how to lose the meat without losing my soul.

First things first: McQuirter disabused me of the notion that transitioning to vegetarianism need be uniquely difficult for African-Americans.

It seems that meat is the one thing on which most members of the American melting pot can agree. The average American, whether Jewish like Jonathan Safran Foer or African American like me, eats something on the order of 200 pounds of meat a year. Nevertheless, there is this point that too often goes unspoken:

“Of course we have unique challenges because of culture and foodways … as any culture does. But to be historically accurate, and based on my own experience, we have a long tradition of being pioneers in healthy eating and veganism.”

McQuirter herself was introduced to veganism in the 80s by African Americans who launched the first vegan restaurant in Washington, D.C. She was also initially influenced by social justice and raw vegan activist Dick Gregory, who was, in turn, taught by natural healer Alvenia Fulton, who opened a natural health food store on Chicago’s South Side in the 1950s.

“We are pioneers in this movement. So, I never let folks assume that this is something new to us and foreign to us, because that’s just not true.

I have been vegan for more than 20 years and I learned from black folks. They taught me how to prepare the food. They taught me why to do it. It was all associated with blackness. It is our very blackness that can lead us to questioning the food that society dictates that we eat, just as we question racism and sexism and capitalism and homophobia and classism.”

McQuirter also reminds me that Coretta Scott King was a devout vegan, as is her son, Dexter King. (Check out A. Breeze Harper’s Sistah Vegan for wonderful discussion on black veganism from a social justice perspective.)

When McQuirter counsels would-be vegetarians, the most common concerns they share transcend race and culture: taste, cost and difficulty in adapting to a radically different lifestyle.

McQuirter reminds these folks that, as omnivores, they already eat vegetarian and vegan foods — veggies and fruits and nuts and grains — everyday. She steers people toward whole, plant-based foods, because packaged, convenience food and analogs can be pricey. She also encourages people to save by cooking at home and from scratch; checking out some vegetarian or vegan cookbooks from the library to experiment. (Two words: Bryant Terry!)

McQuirter encourages newbies, as a first step, to first add more vegan foods to their omnivorous diet. Transition can happen slowly. And there is no need to make the perfect the enemy of the good. The author suggests starting with Meatless Mondays and expanding that observance to a few days a week. She helps newbie plant-based eaters to “veganize” their five to nine favorite meals, allowing them to hold on to favorite flavors and textures. Food is all about the seasoning, McQuirter says. “If you can make a dead bird (chicken) taste good, then you can make anything taste good.” Touche′.

It very hard for folks to comprehend the issues with meat when everything is produced so far away. Nice article

What a great article. Tamara, I love to follow your journey towards health and wellness.